The case citation, arguably the most familiar of legal references, consists of (in the following order and in its most basic form) the names of the parties to the case, the reporter volume, the abbreviated name of the reporter, the page on which the case begins, a pincite (if necessary), and a parenthetical designation of the court and year in which the case was decided. Occasionally, however, the unsuspecting law student will encounter a case citation of an especially peculiar character. These citations include, in addition to the standard attributes described above, a second parenthetical designation consisting of an auxiliary volume number and an obscure abbreviated name. According to Bluebook Rule 10.3.2, "for United States Supreme Court reporters through 90 U.S. (23 Wall.) and a few early state reporters," citations must include ". . . the name of the reporter's editor and the volume of that series."

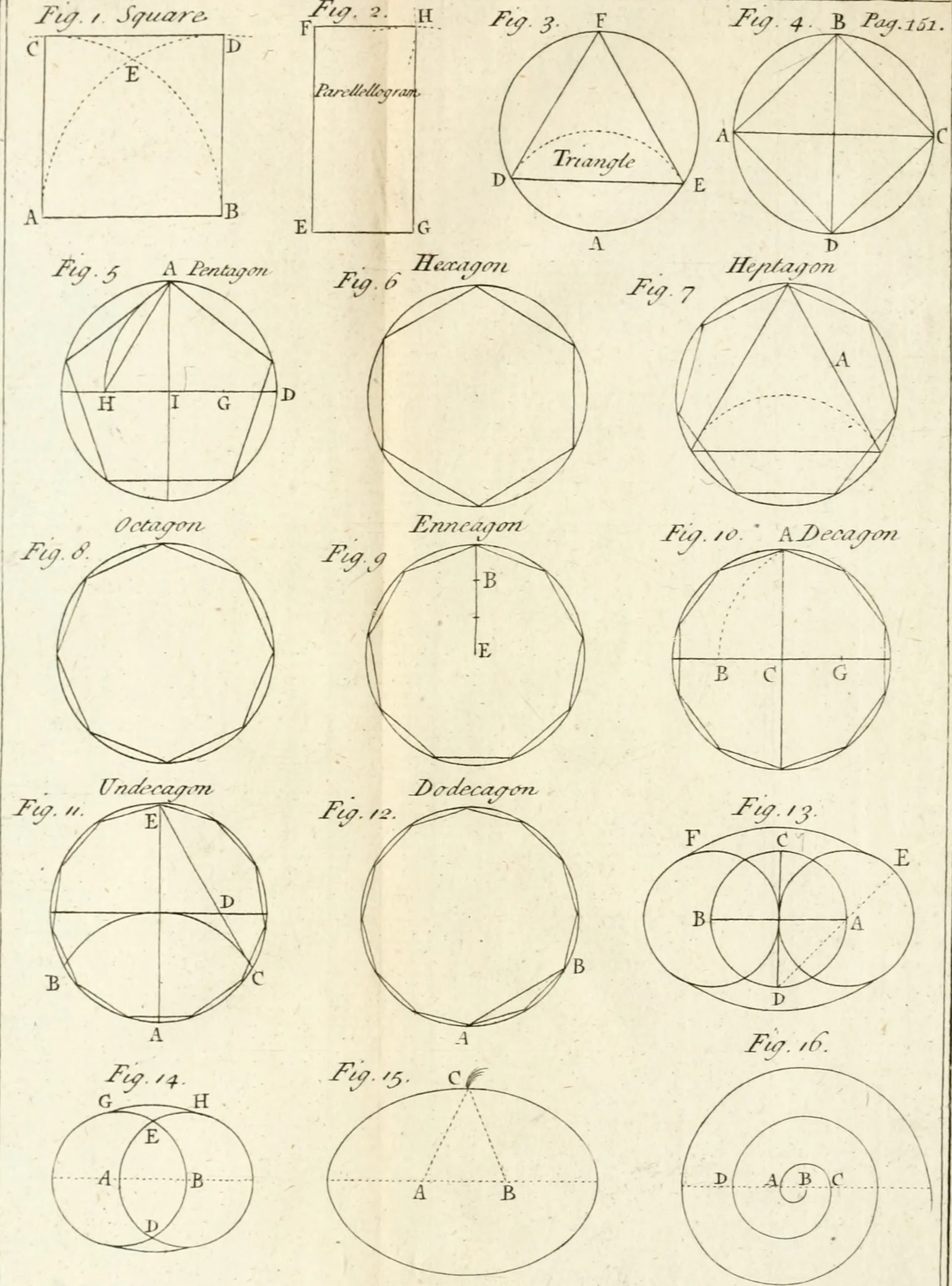

By the late eighteenth century, professional mathematicians across the world had recognized the impossibility of “squaring the circle." In 1897, however, one Hoosier sought to prove otherwise. And Indiana came dangerously close to redefining by legislative fiat a new, mathematically-inaccurate value of Pi "as a contribution to education."

In celebration of Black History Month, the ILA presents a series of biographies examining the lives of prominent black attorneys in Indiana history. Their accomplishments are remarkable not only because of the adversity they faced in life and in practice, but also because of the contributions they made jurisprudentially; as shapers of the law, their legacy defines the normative framework that guides us today.

For over a century, criminal sanctions for drunk driving have characterized American policy. In 1910, the State of New York adopted what is widely considered the nation’s first law prohibiting impaired driving and imposing punishments for such an offense. With the surge in automobile ownership during the 1920s, other states followed suit. And following the repeal of Prohibition in 1933, the increased availability of liquor created an even stronger sense of urgency among public health officials to limit drunk driving. The problem was that early DUI laws were difficult to enforce because they required proof of a driver’s intoxicated state and failed to define the threshold level of inebriation. Lawmakers and public health officials quickly realized the need for a scientific method of analyzing alcohol intoxication. Enter the State of Indiana.