Drunkenness: A Problem of Proof

For over a century, criminal sanctions for drunk driving have characterized American policy. In 1910, the State of New York adopted what is widely considered the nation’s first law prohibiting impaired driving and imposing punishments for such an offense. With the surge in automobile ownership during the 1920s, other states followed suit. And following the repeal of Prohibition in 1933, the increased availability of liquor created an even stronger sense of urgency among public health officials to limit drunk driving. Contemporary statistics supported the growing campaign for stricter laws. In Chicago, for example, the number of injuries and deaths related to drunk driving quadrupled from the previous year. The problem was that early DUI laws were difficult to enforce because they required proof of a driver’s intoxicated state and failed to define the threshold level of inebriation. Lawmakers and public health officials quickly realized the need for a scientific method of analyzing alcohol intoxication.

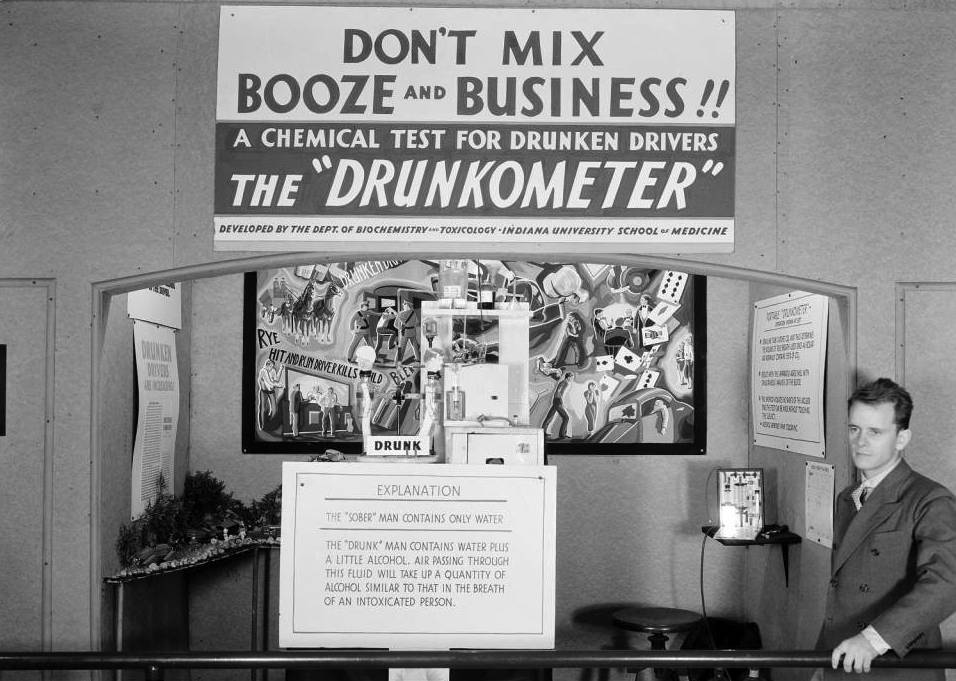

The “Drunkometer”

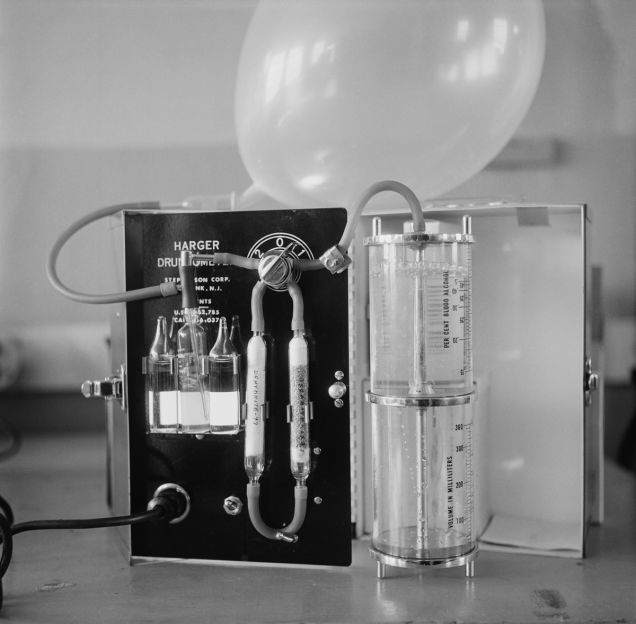

In 1938, Dr. Rolla N Harger, a biochemist at Indiana University, introduced a novel device for measuring a person’s alcohol level. The procedure involved breathing into a balloon, the air in which was then released into a chemical solution that changed a particular color depending on the level of alcohol in the person’s system. The Indiana State Police soon adopted the device, which Harger jokingly referred to as the “Drunkometer.” The name stuck.

"This is Your Police Department" (1951). Public Domain Movie Serials. Use of "Drunkometer" by Detroit Police Department at 4:45 mark.

Indiana LAW sets the stage

In 1938, Dr. Harger also assisted the National Safety Council in drafting a model act providing for the use of evidence from drunkometers and similar apparatus. The legislation also established blood-alcohol limits for motorists: (1) Defendants with a blood-alcohol level of 0.05% or less were not to be considered under the influence; (2) a blood-alcohol level between 0.05% and 0.15% established intoxication but only when taken into consideration with other evidence; and (3) defendants with a blood-alcohol level of 0.15% and above were presumed to be under the influence of alcohol.

In 1939, Indiana became the first state to adopt this model legislation. Under the new measure, if a defendant was alleged by indictment or affidavit to have been under the influence of an intoxicating liquor while driving a vehicle, a court could “admit evidence of the amount of alcohol in the defendant’s blood at the time alleged, as shown by a chemical analysis of his breath, urine or other bodily substance.” This evidence could be "accompanied by other relevant evidence such as eyewitness testimony about the defendant’s appearance, speech and conduct at the time alleged." A blood-alcohol level of 0.15% and above constituted prima facie evidence of intoxication. Levels between 0.02% and 0.15% were "relevant evidence" but not given "prima facie effect." Anything less that 0.02% was "prima facie evidence that the defendant was not under the influence of intoxicating liquor sufficient to lessen his driving ability within the meaning of the statutory definitions of the offenses."

“Evidence that there was . . . fifteen hundredths percent, or more, by weight of alcohol in his blood, is prima facie evidence that the defendant was under the influence of intoxicating liquor sufficiently to lessen his driving ability within the meaning of the statutory definitions of the offenses.”

The statute further provided for certain procedures and penalties. Upon filing an indictment or affidavit, the prosecuting attorney was required to "send to the commissioner of the Bureau of Motor Vehicles an abstract or summary" of the charges. And, upon the defendant's conviction, the statute required the clerk of the court to send to the BMV commissioner "(a) a certified copy of of the judgment, (b) the defendant's driving license or permit, and (c) the court's recommendation that the license or permit be suspended for a specified period of time, not exceeding one year."

The Indiana Supreme Court regularly upheld convictions under the statute against claims of insufficient evidence. For example, in Fielder v. State, 18 N.E.2d 384 (1939), the Court relied on the testimony of two police officers and other bystanders as sufficient to sustain Fielder’s conviction of driving while intoxicated. And in Hunt v. State, 23 N.E.2d 681 (1939), the Court admitted the testimony of police officers who, although not having seen the defendant in his vehicle at the time of the accident, arrested him shortly after when, in his still-intoxicated state, he admitted to having been drunk while driving.

The “Breathalyzer”

In 1954, Indiana once again demonstrated its innovative capacity in fighting against drunk driving. That year, Robert F. Borkenstein, a photographer for the Indiana State Police since 1936, built upon Harger’s work by inventing a more portable and effective device—the Breathalyzer.

According to medical historian Barron Lerner:

The most important advances produced by the Breathalyzer were its small size and portability—it was easily carried and operated by police officers—and its reliability. If operated properly, the results were accurate and replicable. The breath sample passed through an ampule containing acid dichromate . . . which changed colors depending on the amount of alcohol present in the exhaled air.

With Borkenstein’s improvements, Breathalyzer technology quickly became an essential weapon in every police officer’s crime-fighting toolkit.

“Push Button” Justice?

Despite their relative popularity among police departments nationwide, intoxication tests proved controversial among some members of the medical and legal community.

In an article published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal, Dr. A.T. Cameron criticized Harger's apparatus as “crude,” contending that the “expired breath cannot be kept in the rubber bag.” In 1949, Harger defended his work in an article published in the Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology. Harger not only debunked his critics’ theories but also blasted them for not having tested their own claims.

During the 1950s, the criminal justice system—reflecting prevailing attitudes among the American public—proved generally lenient toward drunk drivers. Defense lawyers, of course, frequently attacked the drunkometer’s reliability. The courts, faced with a variety of new scientific advancements—including radar devices for measuring speed—were cautious in admitting evidence of “push button” justice.

Indiana courts, on the other hand, seem to have embraced the new technology. In Ray v. State, 120 N.E.2d 176 (1954), the defendant was convicted by a jury of involuntary manslaughter after he collided with another vehicle driven by twenty-seven year-old Morris Eugene Miller. Miller had been “accompanied by his nine-months old daughter and by his wife,” both of whom apparently survived. Ray, who had consumed at least six beers and had twelve cans with him in the car, was driving “70 to 80 miles per hour in a 30 mile speed zone and on the wrong side of the road.” “The ensuing collision," as the court describes, "demolished the whole left front and side of Miller’s car, which went about fifty feet and jammed itself into a hill.” Ray submitted to a drunkometer test, the results of which were examined by a lab two hours following the incident.

At trial, the State relied on testimony given by Dr. Harger, “a chemist and toxicologist whose extensive learning and vast experience as such was not questioned, and who himself developed the device or scientific instrument known as the drunkometer.” The question presented to him was whether test results would reveal an accurate blood-alcohol percentage when analyzed within the two-hour timeframe. Harger testified in the affirmative, explaining that the percentage “could have been even higher” at the time it was taken.

On appeal, Ray argued that, in the absence of testimony from a medical witness, Miller’s death could have resulted from a pre-existing or intervening cause. The Indiana Supreme Court—clearly incensed by this argument—recounts from the record a gruesomely-detailed description of the scene of the accident. From these facts, the Court concluded, “we think the jury could logically infer that the unlawful conduct of the appellant was the proximate cause of Miller's death.” Ray further challenged the evidence of the drunkometer test and the testimony of Dr. Harger as conjectural. The Court, in affirming the judgment below, found it “permissible for the state to put a hypothetical question to an expert,” the credibility of whom “was for the jury to determine on the basis of his knowledge of the subject.”

recent developments

During 1960s, research in the field of public health prompted changes in legal blood-alcohol limits. In 1964, Borkenstein conducted his landmark Grand Rapids Study, which found definitive evidence linking higher blood-alcohol levels with motor vehicle accidents. As a result, many states, including Indiana (in 1967), reduced BAC limits to 0.10. Four years later, the U.S. Department of Transportation presented to Congress its Alcohol and Highway Safety Report, which concluded that nearly half of all fatal car accidents in the U.S. involved drivers with elevated blood-alcohol levels.

By the mid-1980s, with the growth in anti-drunk driving advocacy organizations such as MADD and SADD, a majority of the American public had come to see driving under the influence as not only dangerous but immoral.

Indiana's current drunk driving statute is located at Ind. Code § 90-30-5.

Timeline of Indiana's Drunk Driving Laws

- 1939: Indiana becomes the first state to enact a drunk driving law based on blood-alcohol levels.

- 1967: Indiana reduces the legal blood-alcohol level to 0.10% and requires blood-alcohol tests.

- 1989: Courts are allowed to order ignition interlock devices on vehicles of persons with drunk driving convictions. These devices require an instant breath test before the vehicle will start.

- 1990: The Indiana General Assembly introduces legislation banning open containers in vehicles and lowering the legal blood-alcohol level to 0.08%. The bills fail to pass.

- 1994: Drivers are banned from drinking while driving and containers in the passenger area are prohibited.

- 1996: A "zero tolerance" policy is established for drivers younger than 21 years of age, making it illegal to drive with even a trace of alcohol in the blood.

- 1997: Consecutive sentences are allowed for drunk drivers convicted of killing more than one person in a crash.

- 1999: Indiana requires minimum sentences of 5 days in jail or 30 days of community service for second-time offenders, and 10 days in jail or 60 days of community service for third-time offenders. Enhanced penalties apply to those with a blood-alcohol level of 0.15% or higher.

- 2001: The law is amended by lowering blood-alcohol levels from 0.10% to 0.08%.

Source: Indiana State Department of Toxicology.

secondary SOURCES

Cameron, A.T. Alcohol and Automobile Driving, 1940 Can. Med. Ass’n J. 46.

Conrad, Edwin. Push-Button Evidence?, 41 Va. L. Rev. 217 (1955).

Harger, R.N. “Debunking” the Drunkomter, 40 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 497 (1949).

Lerner, Barron H. One For the Road: Drunk Driving Since 1900 (2011).

Long, Tony. Dec. 31, 1938: Set ‘em Up, Joe . . . for a Breath Test, Wired.

Novak, Matt. Drunk Driving and the Pre-History of Breathalyzers, Paleofuture.

Rolla N. Harger Dies; Invented Drunkometer, NY Times (Aug. 10, 1983).