On December 11, 1816, President James Madison signed an act of Congress admitting Indiana as the 19th state to the Union. Two hundred years later, the Indiana Legal Archive looks back at the state's history through the documentary lens of photographs, portraits, and artistic renderings.

"Liberty is a basic civil right," Indiana Supreme Court Justice Roger DeBruler wrote in 1972, ". . . It even provides constitutional protection for such personal choices as the style of one’s hair, whether to wear a beard or mustache." Indeed, the right to determine one's personal appearance—whether related to dress or grooming habits—is constitutionally protected from arbitrary government action. But to what extent? Is such a right absolute? Specifically, is the male prerogative to the bristly appendage limited only by his level of testosterone? This essay, in observance of Movember, seeks to answer these questions.

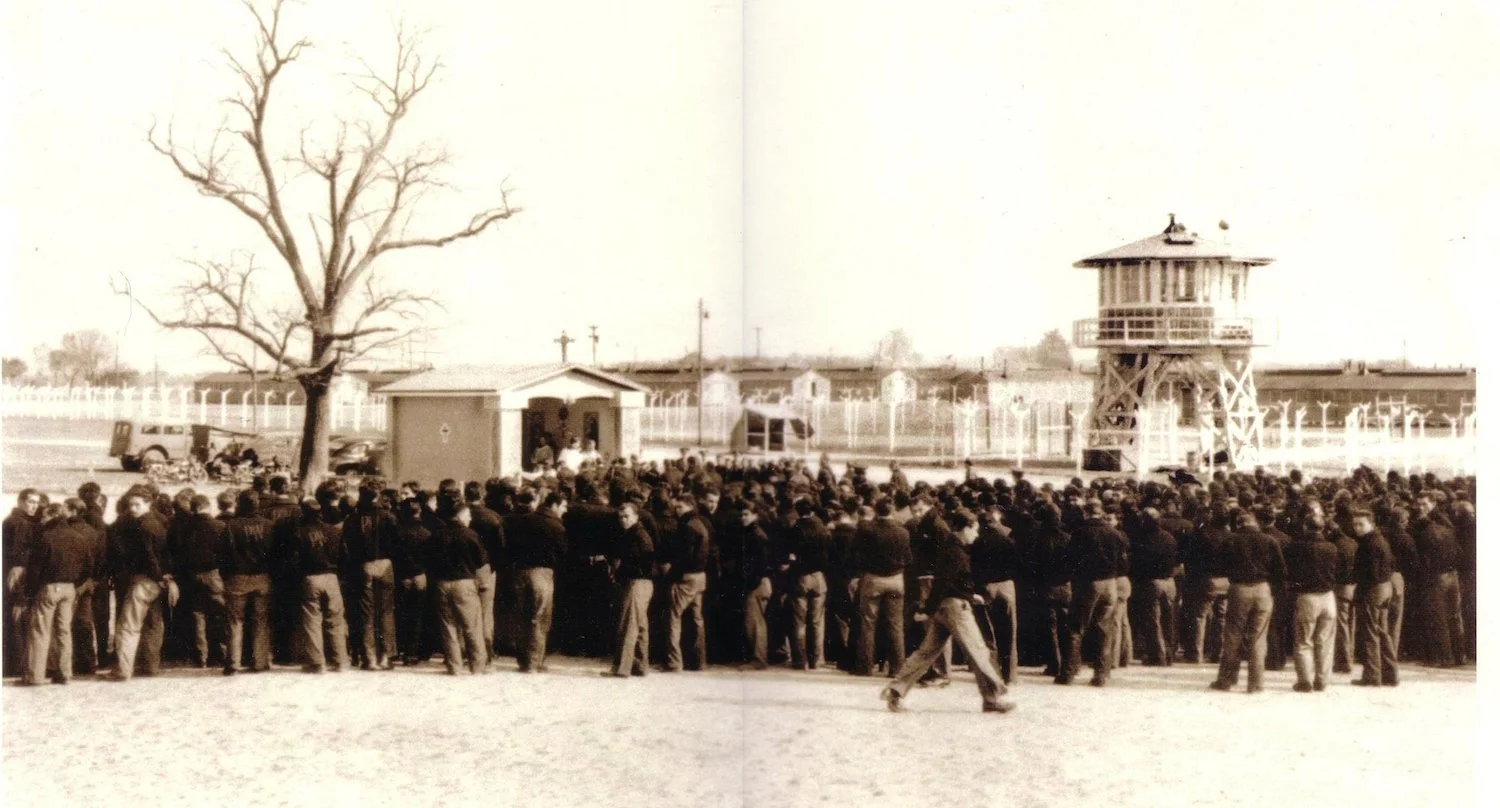

Between 1942 and 1946, nearly half a million enemy prisoners of war—over 425,000 German, 50,000 Italian, and 5,000 Japanese—found their way to one of 511 detention camps across the country. An estimated 12,000-15,000 of these wartime captives landed in Indiana, where they would live and work at one of nine POW camps across the state. What did Hoosiers think of these uninvited guests? How should they be treated? Did they pose a security threat? The domestic presence of a captive foreign enemy during wartime would seem to have provoked a strong abhorrence, perhaps even violent propensities, from their captors. After all, these prisoners had been responsible for the deaths of thousands of American soldiers abroad—the sons, brothers, uncles, nephews, and cousins of countless Hoosier families. Yet the historical record tells a different story.

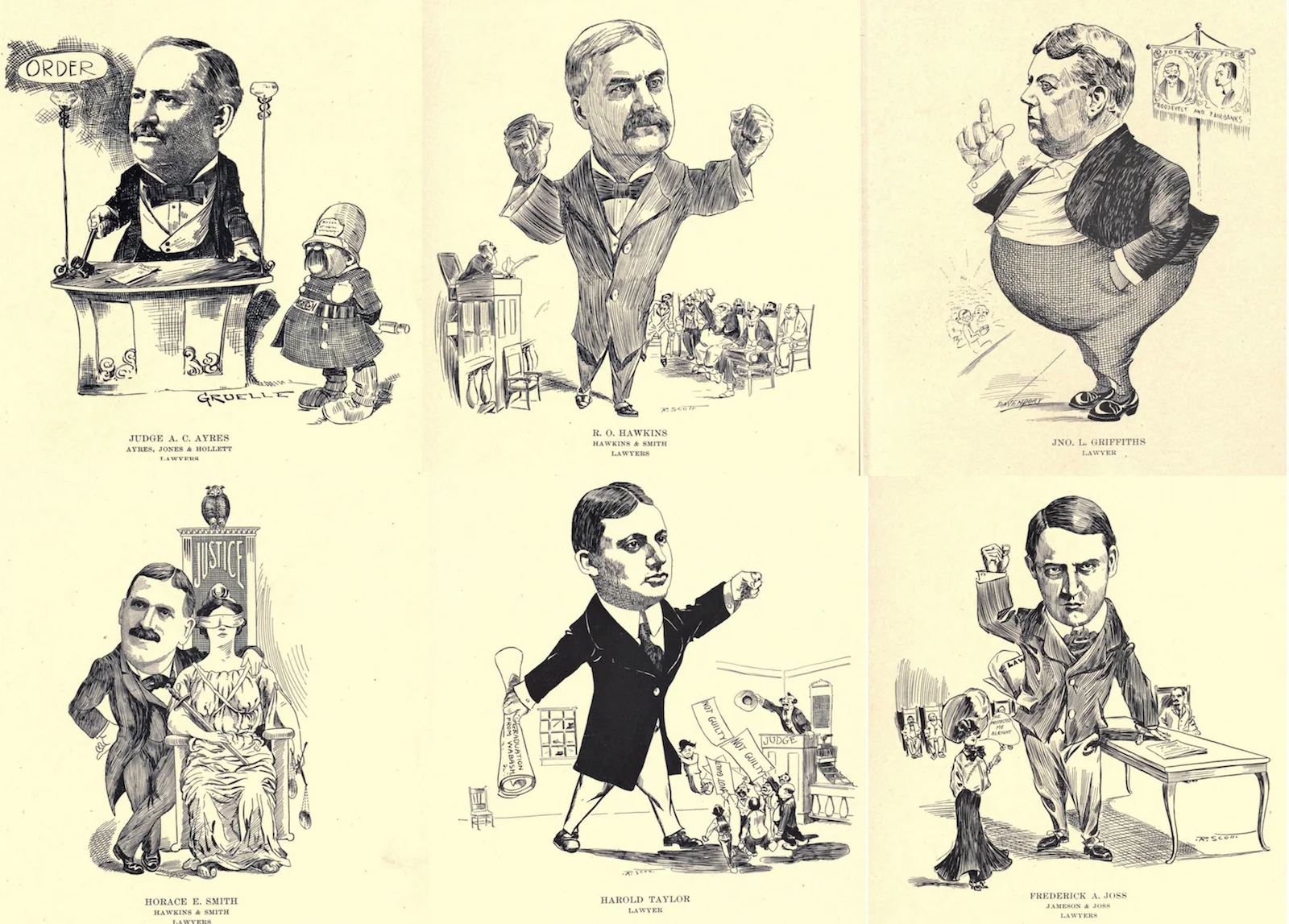

In 1905, the Newspaper Cartoonists’ Association of Indianapolis produced a collection of portraits caricaturing the city’s leading businessmen, government officials, doctors, bankers, civil engineers, and other “men who perform their shares of the world’s work in such a manner so as to bring them into public notice.” Indianapolitans: As We See ‘Em contains 109 full-page, black-and-white portraits of early twentieth-century Hoosier notables, many of which first appeared in local newspapers, including the Indianapolis Star. Among those documented in the book's pages include several prominent members of the Indiana bar. A few names may ring familiar to their modern-day counterparts; most, however, have been lost to posterity. The gallery presented here includes a selection of portraits (slightly refashioned for contemporary viewing enjoyment) depicting these erstwhile jurists.