On August 4, 1932, the National Bar Association—a consortium of black lawyers established in 1924 after its founding members were denied ABA membership—convened at the Walker Casino in Indianapolis for its Eighth Annual Convention. Among Indiana's prominent black lawyers in attendance included Freeman Ransom, NBA Vice President and a member of the Committee on Legislation; Elsie Austin, member of the Committee on Civil Liberties and Politcal Suffrage; Robert Brokenburr, member of the Committee of Jurisprudence and Law Reform; Henry J. Richardson, member of the Legal Directory Committee; and Robert L. Bailey, member of the Budget Committee and Assistant Attorney General of the State of Indiana.

After welcoming remarks from Indianapolis Mayor Reginald H. Sullivan, attorney Perry W. Howard of Mississippi spoke on the challenges faced by black lawyers:

Our colored attorney has a fight that is peculiar. Segregation has a tendency to prevent our receiving a fair deal. Learned as they are in the law, if we ever get what is coming it will have to be through the leadership of the lawyers of this country. From everywhere we have come and met on Indiana soil; we find here the best of our group—the National Bar Association—in the City of Indianapolis.

These words undoubtedly rang true for the small, albeit growing African-American bar in Indiana. Several white attorneys welcomed, and even embraced, their black counterparts. For example, James Ogden—Indiana Attorney General from 1929 to 1933—sponsored Robert L. Bailey’s admission to the Indiana University School of Law in Indianapolis. Both men graduated from the institution in 1912 and Ogden, upon taking public office in 1929, appointed Bailey as Assistant Attorney General. However, as John Clay Smith points out, “attempts by black lawyers to practice in other parts of Indiana were resisted by the white bar.” In 1920, for example, the Evansville Bar Association sought an injunction to prevent Ernest J. Tidrington from becoming a member, and thus preclude him from legal practice in Vanderburgh County. The bar association eventually relented when the court refused to accommodate such racial bigotry in the legal profession. In 1935, Henry J. Richardson, Jr., an Indianapolis attorney and state legislator, became the target of threats from the Ku Klux Klan after introducing a civil rights bill providing for equal rights to public accommodations in Indiana.

The following short biographies provide a glimpse into the lives of some of prominent black attorneys in Indiana history. While only a handful of black lawyers practiced in Indiana during the late 1800s, several others had joined the profession during the first decades of the twentieth century. In 1901, the City of Indianapolis claimed approximately twelve black attorneys, many of whom—including J.T.V. Hill, Gurley Brewer, W.E. Henderson, and J.H. Lott—had established themselves as prominent civic leaders and savvy politicians. By the early 1930s, the presence of black lawyers in Indiana, nearly sixty throughout the state, expanded beyond the capital city into Evansville, Terre Haute, Gary, Richmond, Lafayette, Vincennes, South Bend, and Michigan City.

The lives of these African-American attorneys provide a blueprint for success for all lawyers, regardless of race. A common thread in each of their stories is that their careers lead them to doing more than just practicing law—they facilitated change both locally and nationally.

Though times have changed in many respects from the days of Helen Austin, Zilford Carter, and Frank Beckwith, in others ways they are still the same. Despite calls for diversifying our nation’s law schools, and thus the legal profession, representation of African-American, and minorities in general, remains disproportionately low. And among those who have reached the bar, many are still struggling to become “the first” in areas of the profession. In 2010, Judge Tanya Walton Pratt, an Indiana native, broke the color line in becoming the first African-American federal judge in the state’s history. As black students graduate each spring from one of Indiana’s law schools, many of whom are the first in their families with such a distinction, they too join the struggle.

Dr. Carl Sagan once said, “[y]ou have to know the past to understand the present.” In reflecting on Indiana’s rich legal heritage, all lawyers—whether practicing or aspiring—benefit from the courage and tenacity of their predecessors among the African-American bar, who not only helped preserve the integrity of the profession, but also, as shapers of the law, provided the normative framework that guides us today.

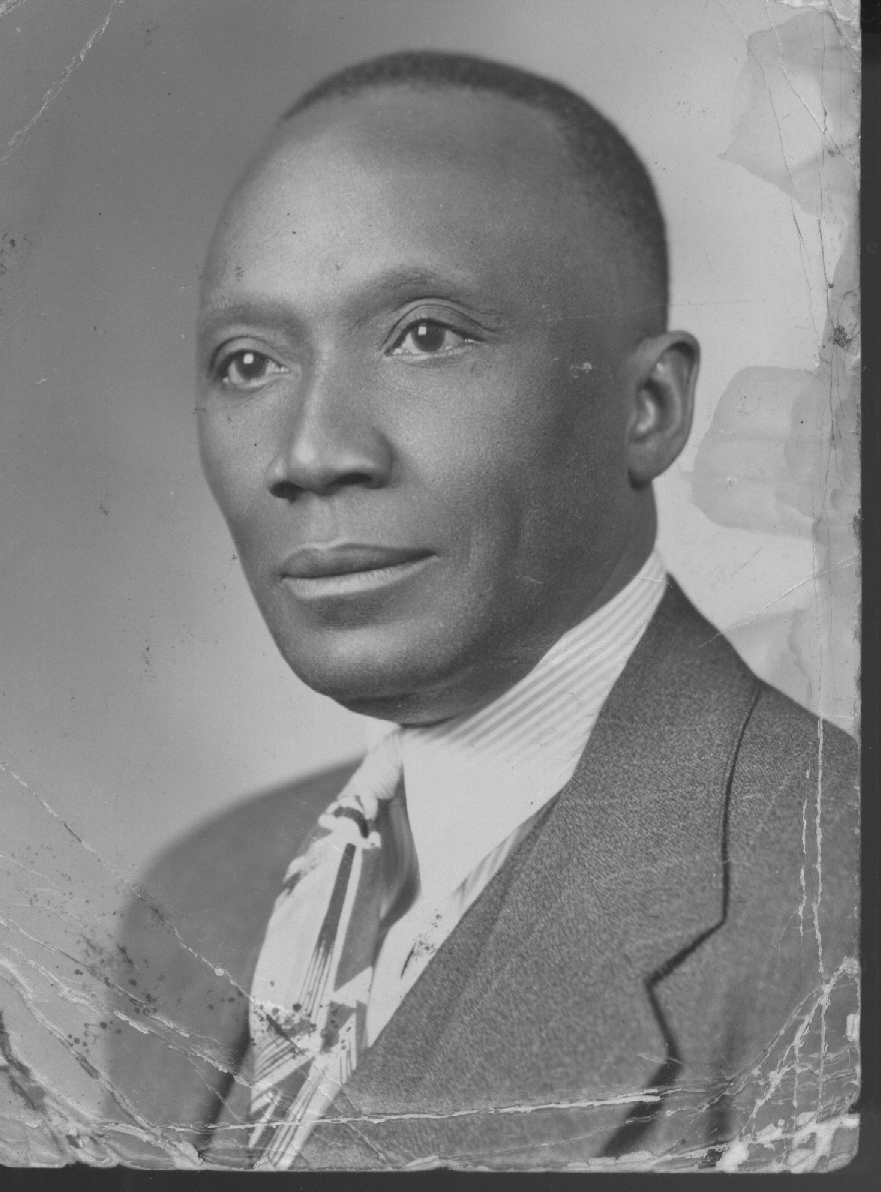

joseph chester allen, sr.

Joseph Chester Allen, Sr. was born Christmas day in 1900. A native of Pawtucket, Rhode Island, Allen earned his bachelor’s degree in philosophy from Brown University in 1923 and his LL.B. from Boston University in 1929. After completing law school, he moved to South Bend, was admitted to the Indiana Bar in 1930, and entered private practice. He served as St. Joseph County Poor Attorney from 1933 to 1936 and, from 1939 to 1941, as state representative with the Indiana General Assembly. During the Second World War, Allen was “coordinator of Negro activities” for the State Defense Council and a member of the Indiana War History Commission.

As chairman of the Indiana Bi-Racial Committee, he played a critical role in integrating African-American labor into the War industry. He broke the color line in becoming not only the first black member of the South Bend School Board, but also the first black president of the St. Joseph County Bar Association. A staunch advocate for civil and public housing rights, he served on the South Bend Citizens Housing Committee and as attorney for the NAACP. Allen is perhaps best known for his unremitting efforts to end segregation at South Bend’s Engman Public Natatorium (the largest swimming pool in the state when it opened in 1922). In 1931, he filed the first complaint to end discrimination at the Natatorium, but not for another nineteen years, in 1950, would the Board of Parks officially integrate the facility. Allen died on May 10, 1980 in South Bend.

elen elsie austin

Helen Elsie Austin was born in 1908 in Tuskegee, Alabama. She later moved with her family to Cincinnati where she received most of her education in public schools. After graduating from Walnut Hills High School in 1924, she attended the University of Cincinnati where she received her B.A. in 1928. After attending one year of law school at the University of Colorado, she returned to Cincinnati to complete her studies in 1930, becoming the first black woman to receive a law degree from the institution.

Following graduation, Austin—having been admitted to the Indiana bar—moved to Indianapolis to practice with Henry J. Richardson, Jr. Although the partnership only lasted for two years, it was the first time that a black woman and man had practiced law together in the State of Indiana. Austin returned to Ohio where, in 1937, she became the first black woman in the United States to serve as assistant attorney general. She later worked as legal counsel for a number of federal government agencies and, from 1960 to 1970, served as U.S. Foreign Service Officer in Nigeria and Kenya. After retiring from government service, she cofounded and operated several educational and cultural programs in Africa. Austin died on October 26, 2004, at the age of 96.

robert l. bailey

Robert L. Bailey was born in 1885 in Florence, Alabama. After graduating from Talladega College, Bailey—like many other aspiring black professionals—moved north in search of better opportunity. In 1912, he received a LL.B. from Indiana University School of Law in Indianapolis. During the 1920s and 1930s, Bailey—for several years, the only black member of the Indianapolis Bar Association—served as a special judge in the Marion Circuit Court, ran for election as a state representative, and belonged to the Legal Aid Society. R.L., as his friends and colleagues called him, enjoyed telling stories and jokes. He drank copiously, smoked cigars, and recited the poetry of Paul Laurence Dunbar. At his office on Pennsylvania Street, according to historian James Madison, “[h]is wooden rolltop desk was always piled high with papers, and although he could never find anything, neither his secretary nor his family was allowed to touch a single thing.”

Early in his career, Bailey argued several successful cases, quickly establishing himself as a skilled lawyer. In 1921, for example, Bailey won an important victory in the “spite fence” case. When Dr. Lucian Meriweather, an African-American dentist, moved into what had been an all-white neighborhood, his neighbors sought to isolate him by constructing tall fences on both sides of his property. Bailey successfully obtained an injunction against the neighbors, forcing them to remove the fence.

In 1931, Indiana Attorney General James Ogden, a friend of Bailey’s during law school, appointed Bailey as assistant attorney general, the first African-American in Indiana to occupy that position. During his time at the AG’s office, Bailey assisted with several important cases, including trials involving conspiracy, blackmail, bank robbery, and murder.

In what was certainly one of his most difficult cases, Bailey, accompanied by his partner Robert Brokenburr, defended James Cameron of Marion, Indiana. Cameron was a sixteen-year-old African-American boy who, along with friends Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith, had been charged with murder, attempted armed robbery, and assault. Cameron claims to have left the scene before the crimes occurred. Yet all three boys—lacking counsel and facing threats by their interrogators—confessed within hours of the crime. On the evening of August 7, 1930, as the boys sat in jail, a lynch mob gathered at the courthouse square seeking vengeance. Cameron, having witnessed his two friends being beaten and hanged, barely escaped the noose himself—an unidentified voice from the crowd attesting to his innocence. Although spared the injustice suffered by his friends, Cameron still faced criminal charges, which meant life in prison or worse, the electric chair, if found guilty. Following a two-day trial in June of 1931—despite the court's exclusion of Cameron's coerced confession from evidence and the inability of the assault victim to conclusively identify Cameron as the perpetrator—an all-male, all-white jury found him guilty as an accessory to voluntary manslaughter, a much lesser charge, but one for which he served two years at the Indiana State Reformatory. It would take another sixty-two years for Cameron to be vindicated of his crimes; on February 4, 1993, Governor Evan Bayh officially pardoned him.

Robert Bailey died in 1940, having suffered a stroke while working in his office. In a tribute to his life, the Indianapolis Recorder published a fitting eulogy for one of Indiana’s finest advocates:

[T]wenty-six years a militant champion for the wronged; his love for battle was surpassed only by his thirst for justice. . . . Above all else persons warmly recount the stories of his titantic [sic] struggles—which almost always ended victoriously—in behalf of an underdog, some person whose rights had been flagrantly violated or his tackling tough cases. Despite his record of never having lost a case for the state during his tenure of office as assistant attorney-general, Attorney Bailey was most widely known and loved because of his brilliant battles for the NAACP, or some deserving person whose funds were low.

frank roscoe beckwith

Born December 11, 1904, in Indianapolis, Frank R. Beckwith graduated from Arsenal Technical High School in 1921. He studied law under the guidance of attorneys Asa J. Smith and Sumner A. Clancy. A devoted public servant, Beckwith acted as the welfare director for the Indiana Industrial Board from 1929 to 1933, served as public defender for the Marion Criminal Court from 1951 to 1958, and was a member of the Indiana Commission on Aging and the Aged from 1957 to 1961. In 1951, Beckwith married Mahala Ashley Dickerson—Indiana’s second black woman attorney—with whom he practiced for a year.

In 1960, Beckwith became the first African American in the history to run for President of the United States. As one of six candidates contending for the Republican nomination, Beckwith’s rivals included New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller, West Virginia Governor Cecil Underwood, Ohio Senator George Bender, and Vice President Richard Nixon. Although voters cast nearly 20,000 votes for Beckwith, the number—constituting a mere one-third of one percent of the Republican ballot—fell far short to compete with Nixon’s party nomination. Beckwith’s bid for public office was neither his first, nor his last. He ran for the state legislature in 1936 and the Indianapolis City Council in 1938. He attempted a second run for the Republican presidential nomination in 1964 while campaigning for Indianapolis mayor the same year.

Aside from his political career, Beckwith was a member of several organizations, including the NAACP and the Bar of the United States Supreme Court. Above all, he was an effective champion of civil rights, demonstrated by his successful efforts in opening Indiana’s high school basketball tournament to black schools and ending employment discrimination at Marion County General Hospital.

Beckwith died on August 24, 1965, in Indianapolis. In 1970, Salem Village Park was rededicated in his honor.

Isidor d. blair

Isidor D. Blair was born January 8, 1869. A native of Charles County, Maryland, Blair attended Morgan College at Baltimore from which he graduated in 1884. Blair later studied law at the University of Michigan, receiving his degree in 1893. Having been admitted to the Indiana bar, he travelled to Indianapolis in 1894 where he opened his new law office. In November of 1902, he was admitted to practice before the Indiana Supreme Court. However, after an unsuccessful bid for justice of the peace, Blair left for California the following year.

robert Lee brokenburr

Robert L. Brokenburr was born in Virginia in 1886. A graduate of Howard Law School, he moved to Indianapolis in 1909 where he partnered with Freeman B. Ransom, another prominent black attorney. A close acquaintance of Madame C.J. Walker—the African-American cosmetics entrepreneur widely held as the country’s first female millionaire—Brokenburr served as general counsel of the Walker Manufacturing Company. During the 1920s he worked as Marion County deputy prosecuting attorney. A member of the National Bar Association, he served on the Committee of Jurisprudence and Law Reform, the Publicity Committee, and the Committee on Affiliations of Bar Associations. “Tall, lean, and always well dressed,” as historian James Madison describes him, “Brokenburr never swore, seldom showed a sense of humor, and loved to listen to classical music.” He lived until 1974, “long enough to enjoy the accolades that came in the 1950s and 1960s to longtime civil rights activists.”

Louis caldwell

Louis Caldwell, according to one historian, was “Gary’s most outspoken black lawyer and local NAACP leader.” A native of Copiah County, Mississippi, Caldwell graduated from the State Normal College of Mississippi in 1903. Travelling north, he attended Northwestern Law School, working as a Pullman porter to help finance his education until he graduated in 1913. In 1915, Caldwell left for Gary, Indiana, where—while waiting to be admitted to the Indiana bar—he worked temporarily for the American Sheet and Tin Plate Company. As an attorney, “[h]e combined the expertise and knowledge of a professional man with the bitter experience of the poor in such a way that he commanded the confidence and respect of a wide range of people.”

Zilford c. Carter

Zilford Carter was born on November 21, 1899, in Mexia, Texas. In 1918, Carter served in the U.S. Army, which included an eight-month assignment in France with the American Expeditionary Force. After receiving his B.S. and LL.B. degrees from Howard University, he was admitted to the Indiana bar in 1924 and entered private practice in South Bend. During World War II, Carter served his country again, this time as a private in the U.S. Quartermaster Corps.

Following the War, Carter became actively involved with the Republican party, winning a seat in 1947 as state representative. After losing the incumbency in 1948, he was appointed by Governor Ralph Gates to the Indiana Fair Employment Practices Advisory Board. In 1951, he became a St. Joseph deputy prosecuting attorney. The following year, he served on both national and state Republican committees campaigning to attract black voters. He was a longtime member of the county and state bar associations, the Knights of Pythias, and the American Legion.

Carter died in South Bend on April 21, 1963.

patrick e. chavis, jr.

Patrick E. Chavis, Jr., was born on July 21, 1921, in Toledo, Ohio. After attending public schools he earned a bachelor’s degree from the University of Toledo in 1944 and an LL.B. in 1947. He later attended Northwestern University. On the advice of a fellow lawyer-legislator, Henry J. Richardson, Chavis moved to Indianapolis in 1947, the same year he was admitted to the bar. He became a partner in one of the first integrated law firms in the city. A Missionary Baptist, Chavis earned a bachelor’s degree in theology from Indiana Christian University and was ordained into the ministry in 1973. Chavis was a Marion County deputy prosecuting attorney from 1948 to 1950, Indianapolis assistant city prosecutor from 1955 to 1958, and Marion County public defender from 1958 to 1962. As a lawyer and a legislator he became recognized as a pioneer in civil rights and labor legislation. He was elected judge of the Marion County Criminal Court only one month before his death on December 18, 1974. In honoring his life, the Indianapolis Star eulogized Chavis as “a strong-willed individual who sets high goals and works hard to reach them.”

harriette vesta bailey conn

A life-long Indianapolis resident, Harriette B. Conn was born September 22, 1922. She was the daughter of famed attorney Robert L. Bailey and his wife Nelle Vesta Hayes Bailey. She studied Latin and history at Crispus Attucks High School, from which she graduated in 1937 at the age of fourteen. Following in her father’s footsteps, she received Talladega College where she received her A.B. in 1941. Conn returned to school several years later, taking night classes and Indiana University School of Law in Indianapolis while raising seven children at home. She graduated in 1955 with a J.D. While in law school, she was the recipient of the first Indiana University Foundation Scholarship awarded at the Indianapolis campus.

Following her admission to the bar, Conn served as an Indiana deputy attorney general from 1955 to 1965, and as a Marion County deputy prosecuting attorney from 1968 to 1970. As a state representative for Marion County between 1967 and 1969, she introduced legislation expanding married women’s property rights. In 1970, she served as state public defender, during which time she oversaw the expansion of the office from a staff of three to twenty-seven attorneys. She served as chairperson of the state advisory committee of the U.S. Civil Rights Commission and as legal counsel to the Indianapolis branch of the NAACP. A tireless worker, she found time for private legal practice, chairing the National Women’s Political Caucus, and other activities. Conn died in Indianapolis on August 21, 1981.

mahala ashley dickerson

Mahala Ashley Dickerson was born on October 12, 1912, in Montgomery, Alabama. Dickerson attended the Montgomery Industrial School for Girls where she met Rosa Parks, establishing a lifelong friendship with the celebrated civil rights activist. In 1935, Dickerson graduated cum laude with a degree in sociology from Fisk University. In 1948, she received her law degree from Howard University. Following her admission to the Alabama bar that summer, she established law offices in Montgomery and Tuskegee. “On my first appearance in court,” she wrote several years later, “I was ordered to the back of the courtroom by an armed sheriff, but left the courtroom instead of going to the back of this segregated hall of justice.” The sheriff apologized when informed that she was licensed to practice in the court; the judge followed suit, travelling personally to her office to extend his regrets.

“On my first appearance in court, I was ordered to the back of the courtroom by an armed sheriff, but left . . . instead of going to the back of this segregated hall of justice.”

After three years of practice in Alabama, Dickerson moved to Indianapolis where she married lawyer and politician Frank Beckwith. Following her admission to the Indiana bar—the second black woman in the state’s history to enjoy such recognition—she practiced for a year with Beckwith before opening her own office. In 1958, following her divorce from Beckwith, she moved to Alaska, where she became the first African American admitted to practice in that state. According to one biographical source, “[i]n all three states, Dickerson was known for her advocacy for the poor and the underprivileged, whether black or white. She accepted many cases for which she received no compensation and served as a mentor to young minority attorneys.”

Described by the Indianapolis Recorder as a “talented and brilliant lawyer” and “an able and witty speaker,” Dickerson took an active role in local civic engagement and as an advocate of civil rights during her time in the Hoosier State. In February of 1953, she petitioned the Public Service Commission to deny requests from Indianapolis Railways, operator of the local public transportation system, for an increase in fares, unless the company agreed to “stop discriminating against Negroes as bus and trolley operators.” In March of 1957, she—along with Willard Ransom and Charles Preston on the Recorder—led a panel discussion on the Montgomery Bus Boycott following a screening of “Walk to Freedom,” a documentary of the event .

In 1983, Dickerson became the first black president of the National Association of Women Lawyers. Two years later, the National Bar Association honored her with the Margaret Brent Award, which recognizes the accomplishments of women lawyers who have excelled in their field and serve as models for other women lawyers. Previous recipients of the award include Supreme Court Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Sandra Day O. Connor.

Dickerson continued practicing law until her death on February 19, 2007, in Wasilla, Alaska.

rayfield fisher

Rayfield Fisher was born August 30, 1940 in Marthaville, Louisiana. Following World War II, he moved with his family to Gary, Indiana, where his father worked at the steel mills. Fisher attended local public schools, graduating from Roosevelt High in 1959. After receiving his bachelor’s degree from Purdue University in 1963, he joined the U.S. Air Force and served until 1967, when he was honorably discharged with the rank of First Lieutentant. Fisher received a J.D. from Valparaiso University Law School in 1973 and was admitted to the bar the following year. Fisher, a Democrat, enjoyed two successful runs for state representative in 1976 and 1978. He suffered defeat in the 1980 primary election, but regained his seat the following February when the legislature removed the successful candidate for failure to meet residency requirements.

wilbur homer grant

Wilbur H. Grant was born December 11, 1897, in New Albany, Indiana. A graduate of Scribner High School in 1916, Grant moved to Indianapolis two years later to study law at Indiana University. He received his LL.B. in 1926 and practiced law until 1976. In 1942, shortly after being elected as a state representative, Grant joined the U.S. Army, but left on temporary furlough to attend legislative sessions.

During his time with the Indiana General Assembly, Grant was the head of the Negro Division of the Republican State Committee and he sponsored several bills to improve the court system and to ban racial segregation. Following his honorable discharge from the Army in 1946, Grant pursued his dedication to public service in a variety of positions. He served as Marion County deputy prosecuting attorney from 1951 to 1958, secretary of the Republican state conventions in 1954 and 1956, and county president of Republican Veterans of World War II in 1964. In 1958, President Dwight Eisenhower appointed Grant to the state advisory committee of the U.S. Civil Rights Commission. He was a Marion County Juvenile Court hearing judge. In 1962 he was elected a Superior Court judge—only the second African American in Indiana history to be elected to the bench—a position in which he served with distinction for twelve years.

Grant died in Indianapolis on August 25, 1983.

forrest w. littlejohn

Forrest W. Littlejohn was born near Asbury, South Carolina, on January 20, 1884. Despite having to work at an early age as a laborer in the cotton mills, Littlejohn completed his primary education at the local public schools and went on to attend the Cowpens Industrial School and Claflin College. He studied law at Howard University in 1911 and received an LL.B. from LaSalle Extension University in 1918. The following yea he moved to Indianapolis to begin a law practice that would last fifty-one years.

Active in politics, Littlejohn was appointed assistant chairman of the Marion County Democratic central committee in 1926, a post he held until 1942. He also served as Marion County deputy prosecuting attorney from 1931 to 1938, assistant Indianapolis city attorney from 1939 to 1942, and Marion County Superior Court special judge. During the Depression, Littlejohn became the first black attorney designated as counsel in a bank receivership case. In 1949, he was elected as state representative. During time with the General Assembly, he introduced bills on housing redevelopment and employment discrimination. Littlejohn lost reelection in 1950. However, two years later Governor Harry Schricker appointed him to an eight-year term on the Boys’ School Parole Board. Dedicated to professional engagement and civic activities, Littlejohn served as president of the Marion County Lawyers’ Club and was a long-time member of the NAACP.

Forrest W. Littlejohn died in Indianapolis on July 24, 1970.

bee longwood

Bee Longwood, an Indianapolis attorney during the 1920s, practiced family law, representing clients primarily in divorce cases. He is listed professionally in City Directories during this period, but the historical record is largely silent on his life and background (an article published in the Black Law Journal in 1983, which mistakenly refers to Longwood as a woman, provides no further information other than his name). According to a notice published in the Indianapolis Star in 1924, Longwood—along with six others—formed the Indiana Democracy League. According to the Star, the purpose of the League was “the promotion of the general welfare of the negro race in the state, to protect the interests of the negro in Indiana educationally, politically, commercially and in other ways, and to assist in the nomination and election to public office of ‘men who are sta[u]nch Americans.’” Longwood, in direct reference to the Ku Klux Klan—which, by 1925, had reached all levels of state authority, including the governorship—asserted that “. . . the sacred and constitutional guarantees of free and lawful assemblage, the freedom of press, freedom of speech and religious liberty, the basic foundation of every American home regardless of creed, color or nationality, has been threatened, and it devolves upon every man and woman to fight with ballots to restore confidence in the constitution and laws and protect his own freedom.”

william davis mackey, sr.

William D. Mackey was born March 23, 1913, in Marvell, Arkansas. At around the age of seven, his family moved to Gary, Indiana, where his father operated a grocery store.

Mackey attended the Gary public schools, graduating from Roosevelt High in 1931. He attended Tennessee State University from 1935 to 1937 and received a B.A. from Allen University in 1940. He graduated from Lincoln University Law School in 1947, and in 1962 he was awarded a M.S. degree by Butler University. After moving to Indianapolis shortly after World War II, Mackey was a manager at a life insurance company and served as a two-term (1951-53) state representative for Marion County. In his legislative capacity he worked to increase funding for the Indiana Fair Employment Practices program. He was a member of the NAACP, president of the Indianapolis Business League in 1950, active in several educational associations and, in 1953, co-chaired the local United Negro College Fund drive. From 1958 until he retired, he taught at Indianapolis Public Schools.

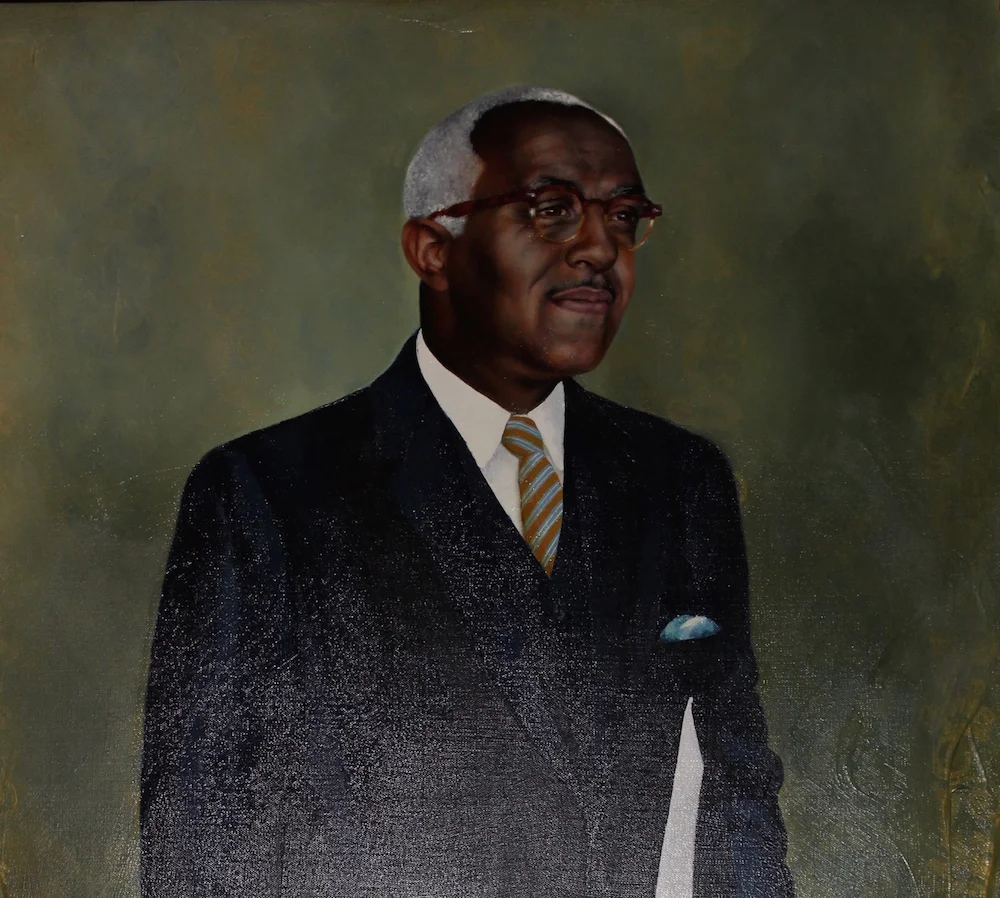

john morton-finney

Born June 25, 1889 in Uniontown, Kentucky, John Morton-Finney was the son of a former slave and one of seven siblings. During World War I, he fought as a “Buffalo soldier,” an all-black unit of the U.S. Army established by act of Congress in 1866.

John Morton-Finney.

After an honorable discharge, Morton-Finney—fluent in Latin, Greek, German, Spanish and French—taught languages for several years at Fisk University in Nashville and Lincoln University in Jefferson City, Missouri. In 1922, he moved to Indianapolis where, five years later, he became the first teacher at Crispus Attucks High School when the all-black academy opened its doors in 1927. “In the era of segregated schools,” the Indianapolis Star wrote in 2009, “Morton-Finney built the foreign languages department at all-black Attucks into one of the state’s finest.” He later taught at other Indianapolis Public Schools.

Over the course of his lifetime, Morton-Finney earned a total of eleven degrees, five of which were in the law—one from Lincoln College of Law in 1935 and another from Indiana University School of Law eleven years later (his other degrees were awarded for mathematics, French, and history). He received his last degree at the age of 75, from Butler University. An avid reader of classical literature, he could recite Homer, Shakespeare, Cicero, and Chaucer from memory. “I never stop studying,” he told the Star, at the age of 104. “When you stop learning, that’s about the end of you.”

Morton-Finney was admitted to the U.S. Supreme Court at the age of 83 and continued practicing law until the age of 107. This amazing achievement (to say the least) led to his induction into the National Bar Association’s Hall of Fame in 1991. He died on January 28, 1998, at the age of 108.

john moss, jr.

John Moss, Jr. was born and raised in Fairfield, Alabama. After graduating from Dillard University in New Orleans, Moss—at the encouragement of Joseph Taylor, later a professor of sociology and first dean of IUPUI’s School of Liberal Arts—moved to Indianapolis to attend Indiana University School of Law. After graduating, Moss taught for a year at what is now Florida State School of Law before returning to Indy.

Moss’s practice focused on civil rights litigation, including employment discrimination, police brutality, wrongful death, and criminal law. In 1968, in response to de facto segregation in Indianapolis Public Schools, Moss—working with the Indianapolis Branch of the NAACP—filed the class-action lawsuit on behalf of all black students to desegregate the schools, ultimately leading to student busing within the district and Marion County township schools to achieve racial balance.

Moss also helped secure a multi-million-dollar gender discrimination judgment against Colgate Palmolive Corp. on behalf of the company’s female employees who had received disproportionate salaries.

In 1989, Moss filed suit for the wrongful death of Michael Taylor, an Indianapolis teen who—two years prior while in police custody—was found dead in the back of a police car with a gunshot wound to his head while in handcuffs. An all-white jury in Hancock County awarded the Taylor family over $3.5 million, which, at the time, was the largest judgment awarded against a municipality in Indiana history.

Moss died on December 26, 2010, at the age of 74.

freeman b. ransom

Freeman Ransom was born in Grenada, Mississippi, where he attended public schools. He studied theology and law at Walden University in Nashville and later pursued graduate studies at Columbia University School of Law. He came to Indianapolis in 1910 where became manager and general counsel for the Madame C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company. “Under his great leadership,” the Indianapolis Recorder wrote in honor his life, “the [Walker] firm did more than make money to pay high salaries and build great buildings. It gave thousands of dollars for YMCA’s, YWCA’s, churches, schools, and scholarships.”

In paying tribute Ransom, Governor Ralph Gates praised him for “[h]is work in behalf of his people, the state and the nation [which] brought him well-deserved recognition as an able and upstanding leader. His life and work in furtherance of the highest ideals of citizenship will remain an inspiration to those he sought to serve.”

Ransom Place, an Indianapolis neighborhood where he and his wife Nettie lived with their children, was named in his honor 50 years following his death.

willard ransom

Following in the footsteps of his father, Willard Ransom was a pioneer in the civil rights movement in Indianapolis. A 1932 graduate of Crispus Attucks High School, Ransom graduated summa cum laude from Talladega College in 1936. Three years later he received his law degree from Harvard University and was admitted to the bar. In 1941, only two months into a four-year term as assistant attorney general, he was inducted into the service. After serving overseas in the Army, he returned to Indianapolis only to encounter prejudice at home. “The contrast between having served in the Army and running into this discrimination and barriers at home was a discouraging thing,” he reflected in a 1991 interview.

As a result of this experience, Ransom reorganized the state chapter of the NAACP, encouraging people across the state to take direct action for civil rights. He organized local protests in the late 1950s, before many of the sit-ins and marches in the South. One protest targeted the bus station at the former Traction Terminal Building located in downtown Indianapolis. “There was a big restaurant there,” he recalled, “[a]nd there were so many blacks traveling on buses. We were insulted in that place because no one would serve us.”

From 1947 to 1954, he was assistant manager of Madame C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company. During this time, he managed a private practice and played a leading role in passing all significant civil rights legislation in Indiana since 1946. In addition to serving five terms as chairman of the state NAACP, he was legal counsel to blacks in the Indianapolis fire and police departments, director of National City Bank of Indiana, and a board member of the Madame C. J. Walker Urban Life Center. And in 1970, he co-founded the Indiana Black Expo. A founding member of the Concerned Ministers of Indianapolis, he received the organization’s Thurgood Marshall Award in 1993 for his dedicated work in the civil rights movement.

Ransom died in Indianapolis on November 7, 1995, at the age of 79.

henry johnson richardson, jr.

Henry J. Richardson, Jr., was born June 21, 1902, in Huntsville, Alabama. Ambitious for an education better than what he could find at home, he left for Indianapolis at the age of seventeen, attending Shortridge High School while living at the YMCA and waiting tables to support himself. After graduating in 1921, he studied at the University of Illinois for two years on a scholarship. He then returned to Indianapolis to attend the Indiana University School of Law, earning his LL.B. in 1928.

Soon after graduation Richardson became active in politics. In 1930, he was appointed a temporary judge in Marion County Superior Court. Two years later, he was elected as a state representative, becoming—along with Robert Stanton—the first of two blacks to sit with the General Assembly in thirty-five years. As a three-term legislator, he authored the first fair employment practices law in the United States. The measure prohibited state or municipal corporations from discriminating in contracting for public works projects. Richardson was also instrumental in amending the state constitution to allow integration of the National Guard and he helped end racial discrimination at Indiana University, which had prohibited blacks from living in campus dormitories.

In 1934, Richardson, along with six other legislators, cosponsored a bill to “prohibit discrimination and intimidation on account of race or color” in all public accommodations. Richardson challenged his colleagues to “put teeth” into the state’s existing civil rights law, a measure enacted in 1885 but largely emasculated by the courts in succeeding years. The denial of rights protected under the law, he declared, was “unconstitutional, un-Christian and anti-social.” While Democrats from Indianapolis and the Calumet region supported Richardson, a majority of legislators—under pressure from lobbyists representing theaters, hotels, and restaurants seeking to defeat the bill—voted against expanding civil rights in Indiana. Not until after World War II would the Indiana General Assembly introduce legislation strengthening the public accommodations law.

Despite this setback, Richardson remained committed to equality and civil rights over the course of his long career, especially in areas of housing and education. He was a leader in campaigning for passage of Indiana’s school desegregation law in 1949. In 1953, he worked with Thurgood Marshall to win an important case for integrated housing in Evansville. In addition to serving as legal counsel for the NAACP, he helped organize the Indianapolis Urban League in 1965 and worked for the Federal Civil Rights Commission from 1964 to 1968. His was a board member of the Indianapolis Church Federation, supported the local YMCA, and served on the Mayor’s Advisory Council and the Greater Indianapolis Progress Committee.

Richardson died in Indianapolis on December 5, 1983.

charles atlas walton

Charles A. Walton was born on June 24, 1936, in Lamkin, Mississippi. At the age of four, he moved with his family to Indianapolis where his father worked for several years as a shipping clerk. Walton attended Crispus Attucks High School, graduating in 1952. He went on to receive bachelor or arts from Morehouse College in 1956 and a J.D. from Indiana University in 1959. Following his admission to the bar the following year, he entered private practice. In 1965, he served as a state representative for Marion County, sponsoring a number of bills dealing with criminal justice reform, the courts, and domestic relations. Prior to his time as a legislator, Walton was a Marion County deputy prosecuting attorney, Superior Court bailiff, precinct committeeman, ward chairman, treasurer of the Marion County Young Democrats, and as county registration chairman. After losing legislative seat in 1966, Walton served as assistant Marion County attorney and continued his private practice. He died in Indianapolis on February 19, 1996.

sources

Attucks Teacher Was the Last of Indiana’s Buffalo Soldiers, Indpls Star (Aug. 26, 2008).

Balanoff, Elizabeth. A History of the Black Community of Gary, Indiana, 1906-1940 (Ph.D. Dissertation, Univ. of Chicago, 1974).

Bates, Joseph Clement. History of the Bench and Bar of California (1912).

Chambers, ed., Lucille Arcola. America's Tenth Man: A Pictorial Review of One-Tenth of A Nation, Presenting the Negro Contribution to American Life Today (1957).

Harmon, David. Mahala Ashley Dickerson, Encyclopedia of Alabama (last updated, May 23, 2011).

Indiana Democracy League is Formed, Indpls Star (July 1, 1924), at 28.

Indiana State Library. Frank R. Beckwith: Biographical Note (May 7, 2013).

January, Alan F., and Justin E. Walsh. A Century of Achievement: Black Hoosiers in the Indiana General Assembly, 1881-1986 (1986).

John Moss Jr. Remembered: Attorney Won Successful Fights for Justice, Indpls Recorder (Jan. 10, 2011).

King, Robert. Scholar-Educator Never Stopped Learning, Indpls Star (Feb. 27, 2009).

Ksander, Yaël, Indiana Public Media. Frank Beckwith For President, Moment of Indiana History (Feb. 14, 2011).

Madison, James H. A Lynching in the Heartland: Race and Memory in America (2001).

Morgan, Roderick. John Morton-Finney: Indiana’s Original Renaissance Man, Bingham, Greenbaum, Doll Blog (Feb. 24, 2011).

Nelson, Jennifer. Indianapolis Attorney ‘Trailblazer’ For Civil Rights, Ind. Lawyer (Dec. 27, 2010).

Smith, Jr., John Clay. The Marion County Lawyers’ Club: 1932 and the Black Lawyer, 8 Black L.J. 170 (1983).

Smith, Jr., John Clay. Emancipation: The Making of the Black Lawyer, 1844-1944 (1993).

Smith, Jr., ed., John Clay. Rebels in Law: Voices in History of Black Women Lawyers (2000).

Styles, Fitzhugh Lee. Negroes and the Law (1937).

Thorbrough, Emma Lou. Indiana Blacks in the Twentieth Century (2000).

Thorbrough, Emma Lou. The Indianapolis School Busing Case, in We the People: Indiana and the United States Constitution (Ind. Hist. Soc'y, 1987).

Warren, Stanley. Robert L. Bailey: Great Man With a Thirst For Justice, 55 Black Hist. News & Notes 6 (Feb. 1994).