Indiana is known for its fair share of celebrity personalities. Hoosier notables such as Kurt Vonnegut, Wes Montgomery, James Dean, Oscar Robertson, Ernie Pyle, and Madame C.J. Walker, exemplify some of the most significant literary, musical, cinematic, sports, journalistic, and business figures in modern U.S. history. Yet there are other, less prominent, individuals whose work has had an equally profound impact (for better or for worse) on American society and beyond. These persons are known not for their musical talents, acting fame, or athletic ability, but rather for the novel product of their intellectual and engineering skills. From Richard Gatling (Gatling Gun) to Hendrix Stukart (bread slicer), these utilitarians developed or improved upon a range of methods and devices, introducing radical breakthroughs in technology or simply making life a little more convenient and entertaining for us all.

“Congress shall have power to . . . promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries.”

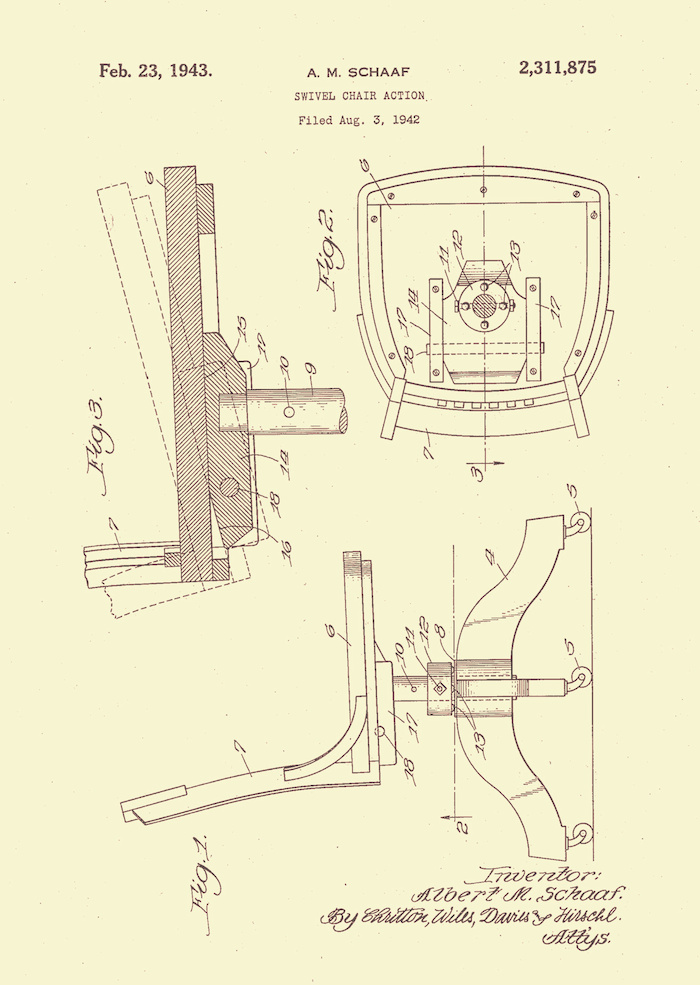

Article I, Section 8, Clause 8 of the United States Constitution grants Congress the power “to promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries.” By virtue of this authority, Congress passed the first U.S. Patent Act on April 10, 1790. The act empowered the U.S. Patent Board to grant or deny a patent for an invention “not before known or used,” should the commission “deem the invention or discovery sufficiently useful and important.” Among other prerequisites, applicants were required to “deliver to the Secretary of State a specification in writing, containing a description” of their invention, “accompanied with drafts or models.” Prior to 1870, the U.S. Patent Office established few uniform specifications for these artistic renderings. Drawings ranged in size, from a half sheet to large folios, and some were drafted with elaborate watercolors. By 1871, the patent office required all drawings to be black on white and of a specific size. Today, the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) specifies the paper size and type, sheet margins, scale, shading (allowing for color on “rare occasions”) and other details relating to the presentation of patent drawings. 37 CFR 1.84.

This gallery of meticulously drafted (and aesthetically pleasing) patent drawings illustrates a small sample of Hoosier ingenuity—from the practical, to the deadly and macabre, to the utterly strange—in the “progress of science and useful arts."

Richard Gatling: Innovator in Firearm Technology

Perhaps the most well-known of these Indiana inventors is Richard Gatling, an innovator in mid-nineteenth-century firearm technology. Born and raised in North Carolina, Gatling worked at the county clerk’s office, taught school, and became a trade merchant. Before achieving repute for his advances in weaponry, he invented a rice-sowing machine and a wheat drill (machines to aid in planting). In 1850, he graduated from the Ohio Medical College but never formally practiced medicine. Gatling later moved to Indianapolis and it was here that he devoted his efforts to the perfection of firearms. In 1861, near the outbreak of the Civil War, he designed the Gatling Gun, a forerunner to the modern machine gun. Gatling patented his design on November 4, 1862. According to the patent specifications, “[t]he object of this invention is to obtain a simple, compact, durable, and efficient firearm for war purposes, to be used either in attack or defence, one that is light when compared with ordinary field-artillery, that is easily transported, that may be rapidly fired, and that can be operated by few men."

Albert Fearnaught: developments in macabre technology

Back in the 19th century, people struggled in finding a sense of closure when burying their deceased loved ones. The potential for grave robbing (a lucrative business at the time due to the difficulty for medical students to legally secure cadavers) and the uncertainties of determining death led to a niche trade in coffin security. To protect against the former of these evils, cemetery guns and grave torpedoes were relatively effective. The greatest fear, however, was premature burial, the possibility of which was not completely out of the question before modern advances in medical technology (the stethoscope wasn’t invented until 1816). Fortunately, several options were available for those not fully inclined to rest in peace. Inventors patented a range of devices—from ringing bells to ventilation systems—for use by the entombed undead. Among these innovators was Albert Fearnaught (a fitting name it seems) of Indianapolis. In 1882, Fearnaught patented the grave signal, a spring-loaded apparatus tied to a person’s wrist that would release a distress flag and ventilate the coffin when activated from below. According to his patent specifications, Fearnaught’s invention provided

“a signal whereby persons who have been buried under the mistaken impression that death had occurred can, upon returning to consciousness, inform the person in charge of the cemetery of that fact, so that they may be disinterred, and at the same time obtain a supply of air.”

It is uncertain whether Fearnaught’s macabre device successfully alerted someone to a resurrection, but it certainly makes for a great anecdote in the history of American inventions. Fearnaught died in 1924. Apparently he (or his family) was confident in his permanent demise, as his grave in Crown Hill Cemetery does not include his life-saving invention.

Edward J. Pennington: Motorcycle Pioneer

Born in Moores Hill, Indiana in 1858, E.J. Pennington was an inventor of several mechanical apparatus, having received patents for stirling engines, ignition systems, and pulley devices. Pennington is probably best known for his pioneering work on “motorcycles” (a term that he apparently coined in 1893). After showcasing his designs in Milwaukee to little fanfare, he sold his patent to The Great Horseless Company in England in 1896. Pennington was known for promoting his creations with grandiose, yet often bogus, claims. While frequently attracting financial support for his projects, Pennington rarely made good on compensating his investors. However, while considered a fraud by many, he never spent time in prison for his unscrupulous business schemes. As the New York Times wrote in his obituary, “his career [was] remarkable for the fact that he rarely got into the toils of the law."

William Urschel: "Eskimo House" Entrepreneur

Hailing from Valparaiso, Indiana, William Urschel developed a new way of constructing just about any type of dwelling. Patented in 1935 as the “Eskimo House,” Urschel’s invention was “to be used in the construction of a novel spherical or partly spherical building,” including churches, schools, gas stations, “tourist huts,” or any other structure “which is economical in construction [and] simple in design, operation, and adjustment.” Considering it's structural versatility, we are left wondering why Urschel's Eskimo House failed to dominate the architectural world.

sources

U.S. Const. art. I, § 8, cl. 8.

Patent Act of 1790, ch. 7, 1 Stat. 109.

Standards for Drawings, 37 C.F.R. § 1.84 (2014).

Campbell-Dollaghan, Kelsey. The Unsung Art of Patent Drawings, Fast Company.

Chang, Alexandra. The History (and Artistic De-Evolution) of Patent Drawings, Wired.

Mitchell, Dawn. Albert Fearnaught and His Signal from the Grave, Indianapolis Star (Jan. 5, 2015).

Novak, Matt. This Concrete Ball Was Supposed to Be the Motel of the Future, Paleofuture.

Prager, Frank D. Historic Background and Foundation of American Patent Law, 5 Am. J. Legal Hist. 309 (1961).

Ptak, John. FearNaughtia Coffins: Life Detectors, Escape Ladders, Breathin' Pipes and Premauture Burial, JF Ptak Science Books (June 25, 2011).

United States Patent and Trademark Office, General Information Concerning Patents.