Introduction

national Origins

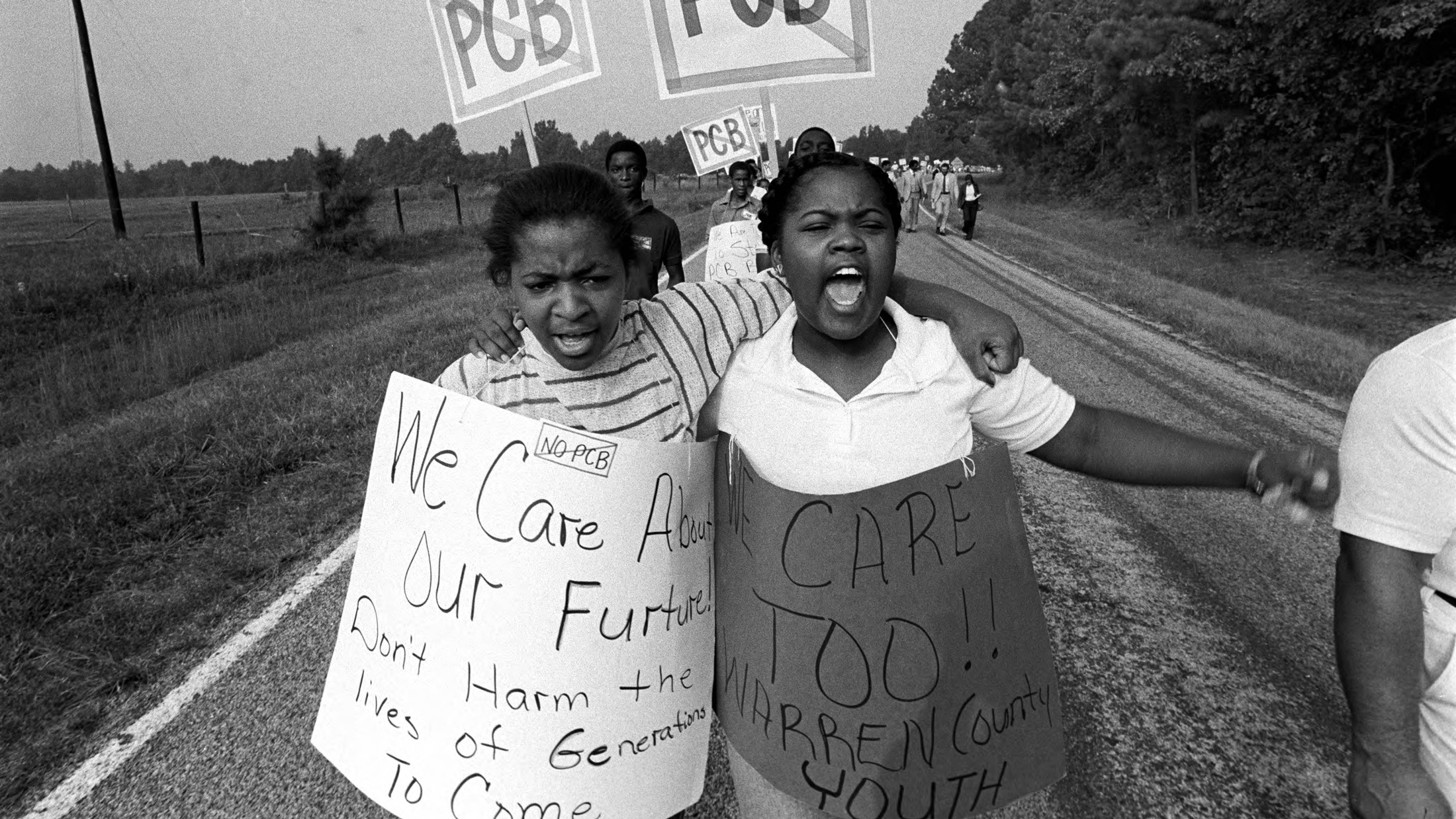

During the early 1980s, the United States witnessed a new environmental campaign taking shape—one rooted in the civil rights and anti-toxics movements of previous decades. In September of 1982, the residents of Warren County, North Carolina marched in protest against the siting of a local polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) landfill. Four years prior, over 30,000 gallons of waste oil contaminated with PCBs were illegally discharged onto roadsides across the state. After the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) designated these sites for remedial cleanup, the state needed a place to dispose of the contaminated soil. In 1979, the North Carolina Department of Environmental and Natural Resources chose the rural, poor, and predominantly black Warren County for the landfill. The local NAACP filed suit in an attempt to block the landfill, but ultimately failed. The first trucks to arrive at the site met with sharp protest, resulting in hundreds of arrests.

Soon, communities across the United States followed suit. Residents from predominantly low-income, minority communities—from Chester, Pennsylvania and Camden, New Jersey, to Los Angeles, California and the small parishes along the Mississippi River between Baton Rouge and New Orleans—protested local government decisions to license the siting or expansion of landfills, hazardous waste facilities, and other environmentally-unfriendly land uses near their homes. Through grassroots organizing and civil rights activism, the quest for environmental justice had begun.

DEFINING THE MOVEMENT

The environmental justice movement emerged in response to an alarming amount of evidence that low-income communities of color are not only burdened with a disproportionate share of environmental hazards, but also less likely to enjoy the environmental and human health benefits of parks, recreation, public sanitation, and other quality-of-life factors because of expense or disproportionate allocation of public resources. So the question arises: is the environmental justice movement concerned with ecological preservation (i.e., going "green") or the promotion of public health?

Traditional environmental organizations such as the Sierra Club, Natural Resources Defense Council, and National Wildlife Federation—while distinguished from each other by unique goals and practices—share a common history that extends from the “back-to-nature” principles of the 19th-century conservation movement. In response to rapid industrialization of the nation’s urban centers, conservationists such as John Muir and Gifford Pinchot sought to prevent what they considered the imminent loss of the nation’s natural resources. With a cynical eye toward the indiscriminately wasteful practices of American industry, these early conservationists viewed the city as an environmental nuisance rather than a potential solution to ecological degradation. In short, the conservation movement of the late-nineteenth century “had no place in its nature-focused ethos for direct confrontation with urban life and no consideration for the problems of the poor, much less the problems of the people of color.”

As the conservation movement gained force, urban living conditions during the late-19th century, which deteriorated rapidly from industrial pollution and the failure of public sanitary systems to accommodate an increasingly dense urban society, stimulated a growing public health movement in the United States. Unlike the conservation movement, the campaign for public health made a distinct connection between the environment (both natural and built) and the physical well being of humans. While distinctions between the two movements have, in recent decades, become blurred—especially in areas related to lead poisoning, municipal water treatment, and air quality—an anti-urban bias continues to pervade the underlying philosophy of the major environmental organizations today.

With its health and human-oriented approach, environmental justice emphasizes the interaction between the physical and natural world. In this sense, “environment” concerns not only the ecological preservation of natural resources, but also the protection of healthy living spaces—the daily settings where people live, work, play, worship, and go to school. Accordingly, EJ advocates seek to prevent environmental threats in housing, land use, industrial sitings, health care, and public sanitation services.

the federal response

In response to the events of Warren County and mounting concerns over environmental inequity, several studies were conducted to examine the siting of environmentally hazardous landfills and the demographics of the host communities. In 1983, following congressional approval, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (U.S. GAO) released Siting of Hazardous Waste Landfills and Their Correlation with Racial and Economic Status of Surrounding Communities. The study revealed that 3 of 4 off-site commercial hazardous waste landfills in the EPA’s Region 4 (composed of 8 southern states) were located in predominantly African-American communities, although African-Americans made up only 20% of the region’s population. Four years later, the United Church of Christ Commission for Racial Justice (CCCRJ) published Toxic Waste and Race in the United States. The investigation found that race was the most potent variable in predicting where waste facilities would be located—more powerful than poverty, land values, and home ownership.

executive order 12898

In 1994, President Bill Clinton issued Executive Order 12898, Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations. With a goal of achieving environmental protection for all communities, the Executive Order places special emphasis on the environmental and human health effects of federal action on of minority and low-income populations. In meeting these ends, the Order specified the creation of an Interagency Working Group on Environmental Justice, directed research and analysis of human health and environmental hazards, and underscored public participation and access to information in the environmental decision-making process.

The Presidential Memorandum accompanying the Order highlights existing laws to “ensure that all communities and persons across th[e] Nation live in a safe and healthful environment.” Specifically, the memo focused on Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). Title VI prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, and national origin in programs and activities receiving federal financial assistance. NEPA requires federal agencies to consider the environmental impacts of their proposed actions and reasonable alternatives to those actions. Procedural provisions under NEPA further require periods for public commenting, which the lead federal agency proposing the action must consider in the planning process.

environmental justice at the epa

In 1998, the EPA established its own definition of environmental justice, which embraces “the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.” Further, the “goal for all communities and persons across this Nation . . . will be achieved when everyone enjoys the same degree of protection from environmental and health hazards and equal access to the decision-making process to have a healthy environment in which to live, learn, and work.”

“Environmental Justice is the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.”

progress and impediments

The explicit recognition of environmental inequities by the federal executive provided the EJ movement with a strong sense of accomplishment. Yet despite these promising measures, other developments severely limited genuine environmental equality as a matter of law and policy. In 1992, Representative John Lewis and Senator Al Gore proposed the Environmental Justice Act. The bill (H.R. 2105, 103rd Cong.) was intended to “establish a program to assure nondiscriminatory compliance with all environmental, health and safety laws and to assure equal protection of the public health.” Despite the support of 44 co-sponsors, the bill died following a series of subcommittee hearings. The following year, the Act was redrafted and reintroduced (S. 1161, 103rd Cong.) by Representative Lewis and Senator Max Baucus. Again, the bill died after committee referral.

Beyond the federal legislative arena, environmental justice claimants have encountered mixed results in the courts. The majority of successful claims originate in traditional common law nuisance theories or under environmental laws such as the National Environmental Protection Act. On the other hand, claims alleging equal protection violations under the Fourteenth Amendment have largely failed because of the high evidentiary burden of proving racial motivation or discriminatory intent. Despite recommendations set forth in the Clinton Memorandum, complaints alleging disparate impact discrimination on the basis of race in violation of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 have likewise proven futile. In 2001, the U.S. Supreme Court held in Alexander v. Sandoval, 525 U.S. 275, that no private right of action existed to enforce disparate-impact regulations promulgated under Title VI.

At the federal administrative level, the EPA has been particularly slow in developing a framework for investigating and acting upon claims of discrimination. In addition, a 1992 investigation by the National Law Journal revealed compelling evidence of racially inequitable enforcement of federal laws and cleanup efforts by the EPA.

the state response

In response to governmental efforts at the federal level, and expanded grassroots organizing at the local level, many states have developed programs to address environmental justice concerns.

The states have proven especially innovative in confronting EJ issues—undertaking a variety of collaborative, problem-solving approaches; encouraging community participation and education initiatives; and implementing creative land-use techniques to reduce health risks and prevent environmental degradation. While progress varies widely, the states provide a potential alternative forum for redressing inequitable environmental burdens. The Public Law Research Institute at the University of California, Hastings College of Law publishes Environmental Justice For All: A Fifty-State Survey of Legislation, Policies and Cases, currently in its 4th edition (2010), a resourceful tool in monitoring EJ developments across the United States.

indiana

Indiana’s environmental justice program took shape in 1996. That year, EPA’s Region 5 (which, in addition to Indiana, includes the states of Illinois, Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio, Wisconsin, and 35 Native American tribes) designated northwest Indiana as one of its “geographic initiatives.” According to Region 5’s 1996 Agenda for Action:

Northwest Indiana, spanning the southern shore of Lake Michigan, has experienced a century of severe environmental degradation. This is largely because of the steel and petroleum refining industries, because of alteration of the natural ecosystem by filling of dunes and wetlands, and because of overall development. Ozone and particulate nonattainment, 10 million cubic yards of contaminated sediments in the Indiana Harbor Ship Canal and the Grand Calumet River, millions of gallons of free-floating petroleum products in the ground-water, and numerous sites contaminated with hazardous waste—including 15 Superfund sites—are some of the many environmental challenges facing the area.

In October of the following year, the EPA announced the winners of its Environmental Justice Community/University Partnership Grants, which allocated over $2 million to eleven individual projects throughout the United States. According to the EPA press release:

The program was established to help minorities and low-income communities address local environmental justice issues through formal partnership agreements with colleges or universities. The winners have created projects that will increase environmental awareness, expand community outreach and provide training and education to socio-economically disadvantaged communities impacted by environmental hazards.

Among the grant recipients was Indiana University Northwest, which used the funds to establish the Northwest Indiana Environmental Justice partnership and Resource Center (EJRC). The mission of the EJRC was to (1) research evidence of an environmental “disproportionate impact” on core urban communities in Northwest Indiana; (2) create a partnership between IU Northwest and community organizations concerned with environmental issues in the urban core of northwestern Indiana; and (3) provide residents with information and data relating to environmental issues in urban areas of the region. Although the EPA grant ended in 2003, the Center continued for several years to facilitate EJ activities in the region through funding from the IU Northwest Library Data Center.

In 1998, IDEM received an EPA environmental justice grant, providing the momentum for a state-wide initiative. Two years later, the Indianapolis Urban League’s Environmental Coalition—the recipient of an environmental justice “small grant” from the EPA—published a study on the relationship between race, income, and toxic air releases. The study, which further prompted IDEM to address EJ issues, concluded that

[b]oth low-income residents and black residents (who make up 90 percent of the minority population) are disproportionately located near TRI (toxic release inventory) facilities in Indianapolis, Indiana. As a result, these populations may face greater health risks from hazardous air emissions.

In 2000, IDEM convened the Interim Environmental Justice Advisory Council—a stakeholder-based group comprised of citizens, environmentalists, academics, and industry representatives from across the state—to assist in developing an EJ Strategic Plan. The Plan, adopted in August 2001, offered a vision statement: "No citizens or communities of the state of Indiana, regardless of race, color, national origin, income or geographic location, will bear a disproportionate share of the risk and consequences of environmental pollution or will be denied equal access to environmental benefits."

“No citizens or communities of the state of Indiana, regardless of race, color, national origin, income or geographic location, will bear a disproportionate share of the risk and consequences of environmental pollution or will be denied equal access to environmental benefits.”

In fulfilling this vision, the agency’s mission statement specified that IDEM collaborate with state communities to ensure development and implementation of policies, programs, and procedures that

Inform, educate and empower all people in our state to have meaningful participation in decisions which affect their environment;

Reduce any cumulative disparate impact of environmental burden, including burdens from past practices, on people of color and/or low-income status; and

Address IDEM’s obligations under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The Plan also contained several goals, including: (1) identification of geographic areas of EJ concern; (2) community education on EJ issues, public participation in environmental decision-making, and the agency’s statutory responsibilities; (3) ensuring opportunities for affected parties to communicate their concerns to IDEM on facility permitting and other decisions involving EJ issues; (4) IDEM staff education; (5) evaluation, with community input, of the effectiveness and appropriateness of existing public processes for environmental decision-making; and (6) involvement of other state agencies (e.g., Indiana Department of Transportation) in EJ discussions to assist in developing their own programs.

Other IDEM initiatives utilizing the EPA EJ grant included GIS mapping, a Guide to Citizen Participation (originally published in English and Spanish), and a brochure on How to Participate in Environmental Decision-Making. The agency's EJ mapping project—which used census data on the state’s demographics and GIS software to collect information on Superfund sites and hazardous waste facilities—helped identify the proximity of low-income and minority residents to environmental hazards.

In 2006, IDEM adopted its first environmental justice policy. The policy, amended in 2008, identifies EJ as including the "fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people in the implementation of environmental decision-making pursuant to all Federal and State environmental statutes, regulations and rules." Accordingly, IDEM endeavors to ensure that all members of the public have (1) equal access to pertinent agency policies and procedures; (2) adequate notice of agency program information and decision-making processes; and (3) opportunities for commenting and providing information to agency staff.

recent developments

For nearly 20 years, the State of Indiana has made great strides in promoting environmental justice. And the state's contributions to the national EJ movement have not gone unnoticed. In 2002, the National Academy of Public Administration—a congressionally-charted non-partisan organization—published a report on the environmental justice efforts of four states, which identified Indiana as one of four "models for change."

While Indiana's early EJ contributions warrant praise, the state's program is not without deficiencies. IDEM's 2006 EJ policy, among other things, affirms the importance of meaningful public participation in the environmental decision-making process, emphasizes adequate public notice of agency activities through communications other than English, and seeks to broaden an "institutional awareness of differences in local conditions and population groups." Overall, however, the policy represents a general departure from the agency's initial focus on low-income, minority populations. Rather, as noted in the PLRI Survey, "it promotes the idea of participatory democracy by all affected populations."

Access to information—whether related to the environmental decision-making process, potential environmental hazards to local communities, or other matters—is a core principle of the EJ movement. Many of IDEM's early initiatives, such as the Guide to Citizen Participation, indicated the importance the agency placed on this principle in developing its EJ program. Recently, IDEM seems to have fallen short in prioritizing access to information. In particular, the Guide is currently unavailable. According to its website, "IDEM is presently working on many updates to the document." However, "a timeline for completion of the new Guide for Citizen Participation has not be established." Another issue relates to the structure and organization of IDEM's website. While the site as a whole contains a variety of information on environmental education and how to protect your home and community, the agency's environmental justice webpage is severely limited in its resources, providing links only to IDEM's internal EJ policy and a handful of documents from the EPA and a single NGO.

udpates

As the environmental justice movement in Indiana matures, the ILA will report back on state and local developments, so check this page frequently for future updates.

sources

Bullard, Robert D., ed. The Quest for Environmental Justice: Human Rights and the Politics of Pollution (2005).

Rechtschaffen, Clifford, Eileen Gauna & Catherine A. O’Neil, Environmental Justice: Law Policy & Regulation (2d ed. 2009).

Rhodes, Edwardo Lao. Environmental Justice in America: A New Paradigm (2003).